Despite so much evidence to the contrary there still remain a few agronomists who seem to be fixated on the link between water soluble phosphate and soil phosphate availability.

This should concern us all as they may be misleading British farmers. They are possibly depriving them of the opportunity for a more cost effective renewable phosphate source in favour of more expensive environmentally unfriendly imported alternatives.

The phosphate in Fibrophos PK Fertiliser has been rigorously tested under the EU and UK fertiliser regulations. It has been proven to be available to the plant as required.

Trials have shown this to be the case across a range of soil types and for more than just one season. It has been the sole source of Phosphate and Potash for many UK farmers over the past 25 years, with the added bonus of a wide range of secondary and trace elements at no extra cost.

These facts are strongly supported by a recent report published in Potash News Feb 2019, produced by the very experienced and highly respected agronomist Johnny Johnston. He has been involved in some very long term experiments at Rothamsted and elsewhere and we summarise his main points below:

Phosphate fixation

Johnny believes that the word ‘fixation’ is misleading when describing the reaction of phosphates when applied to soil. It implies ‘fixed’ phosphate is not available to plants – which is then even more “unhelpful and misleading” when it is changed to ‘locked-up’. He suggests a more appropriate word would be ‘retained’.

The implication that fixed phosphate was unavailable for crops appears to have been widely used by some agronomist ‘to persuade farmers’ that it was essential to apply water-soluble phosphate fertiliser for every crop, and ‘not to buy alternative types of inorganic phosphate fertilisers’.

It has been often said that only 10-15% of applied water-soluble phosphate fertiliser is taken up by the crop to which it was applied, and the rest remains fixed in the soil where it is not available for uptake by plant roots. The remaining 90-85% of the phosphorus in the crop has come from available phosphate in soil supplies. However, if these statements were true and that applied phosphate became fixed in the soil, then where has this readily available soil phosphorus come from?

The truth is that most UK soils contain little plant-available “native” phosphate, so the soil phosphorus taken up by crops must come from reserves accumulated from past phosphate applications. Clearly these reserves have not been fixed irreversibly in the soil as shown by the results from an experiment at Rothamsted. Some of the phosphorus applied as single superphosphate, which is water-soluble, to soils between 1856 and 1901 has been retained in the soil and is still being slowly released and taken up by crop roots.

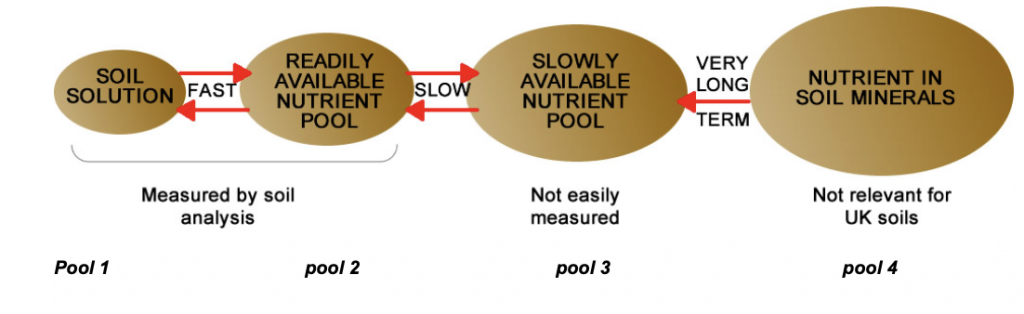

Phosphate Pools

A way of visualising the behaviour of soil phosphorus is to think of it existing in four pools of different availability to crops and with reversible transfer of phosphorus between the pools.

The phosphorus that is immediately available for uptake by plant roots is that in the soil solution (pool 1) and the amount is very small. There is more phosphorus in pool 2, and this phosphorus is readily transferred to pool 1 as the amount of phosphorus there is depleted when taken up by roots. The phosphorus in pools 3 and 4 has low immediate availability and very low availability, respectively. (By analogy to money and its availability, there is cash in the pocket (pool 1), cash in the current account (pool 2), cash in bonds, stocks and shares and least available in the short term, money in land and bricks and mortar (pools 3 and 4 respectively)).

When a phosphate fertiliser, even a water-soluble one, is added to soil only a very small amount stays in the soil solution (pool 1) and the rest transfers to the other pools at varying rates depending on the type of fertiliser and on soil properties. Because there is rapid transfer of phosphorus between pools 1 and 2 the amount of phosphorus in these two pools is often a good indicator of the immediate plant-availability of the phosphate in the soil. Thus, it is this amount that is determined by soil analysis using various reagents that have been shown to correlate well with crop response to soil and applied P. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, Olsen’s method is widely used. The phosphorus that transfers to pools 3 and 4 is slowly available but is not fixed irreversibly in soil, as shown by the results of the experiment mentioned above.

Target Indices

The general advice today to optimise the efficient use of phosphate in most arable crop production is to raise soils to P Index 2, the critical level, and then maintain them at this level by replacing the phosphorus removed in harvested crops.

For those situations where there is a combination of very low soil indicies and a demanding crop such as potatoes, water- soluble phosphate offers the quickest response. However, these circumstances are quite rare so in most cases it would be commercially better to use a less soluble cheaper phosphate fertiliser, but still NACS soluble, applied at the appropriate rate to maintain a soil at P Index 2.

However, Johnny Johnston offers sound advice that it is essential to sample each field every three or four years to ensure that the phosphate fertiliser or phosphate source is maintaining the appropriate level of plant-available phosphorus. Choosing which source to use will depend on its ability to maintain the required critical level of Olsen P for the crops grown, and the cost and availability of the phosphate to achieve this aim.

Summary

As Johnny Johnston has said, it is vital that in order to manage your soil phosphate effectively for a rotation it relies on an understanding of how soil phosphate chemistry works but it is also crucial to understand your specific soil types and crop phosphate needs across your rotation as different crops have different need and modes of accessing the nutrient. Efficiently testing your soils is a good starting point.

Soils: Critically, soils do not lock up phosphates but retain them for later release. The form that they are retained will vary depending on the soil type and the other nutrients within the soil. For example, calcareous soils are more likely to retain the phosphate as calcium phosphate, whereas acidic soils with higher proportions of iron or aluminium are likely to retain phosphate in these forms.

Crops: The form which predominates in soils will have implications for crops trying to access this phosphate, and different crops are able to tap into these resources with differing efficiency. For example, oilseed rape may not be particularly adept at accessing aluminium or iron phosphate, but it does have a greater ability to tap into the reserves of calcium phosphate in soils. This is likely to be due to the acidifying ability of the root exudates close to root tips.

Over 1.5 million tonnes of Fibrophos PK Fertiliser has been applied to UK soils over the past 25 years helping to maintain the nation’s soil P & K indicies.

We think that fact alone is testimony to the efficacy of Fibrophos PK Fertiliser and the commercial judgement of the British farmer.